As for us, our duty is clear. We should not only obey the complete Gospel, but we should teach it to others. We must accept the faith once delivered to the saints, and keep the ordinances as they have come down to us through the New Testament. While we dare not forbid those who teach and obey but half of the Gospel, we may do well to commend them for the good they do. But it is one thing to commend them for the good they do and quite another to encourage them in the neglect of many of the plain commandments. ((Our Relation to Others Engaged in Good Works,” The Gospel Messenger, January 7, 1905, 9.))

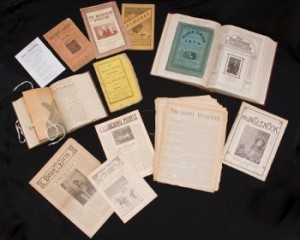

Suppose you wanted to see how Brethren used the beloved phrase of Jude 3 in its booklets, tracts, and papers. As late as 2010, this would have involved having to physically travel to a Brethren library or archive, look through catalogs and finding aids, and then thumb through issue after issue of material. If you were lucky, you could perhaps have microfilm of a Brethren publication sent to your local library, to which you would have to scroll page after page in a similar fashion. However, thanks to the work of the Brethren Digital Archives, many of these publications are now freely accessible and searchable on the internet.

Begun in September 2007, the mission of the Brethren Digital Archives is to digitize some or all of the periodicals produced from the beginning of publication to the year 2000 by each of the Brethren bodies who trace their origin to the baptism near Schwarzenau, Germany in 1708. It consists of twenty partners: archivists, librarians and publishers from every Brethren branch. To date, Brethren Digital Archives has digitized over seven hundred items, including full runs of major publications such as Messenger (beginning Henry Kurtz’s Gospel-Visiter and its variations), The Brethren Evangelist, Brethren Missionary Herald, and Bible Monitor.

One may wonder for the need of a small, volunteered powered organizations like Brethren Digital Archives to form and scan materials. After all, the Google Books Library Project has scanned 20 million book volumes of an estimated 130 million volumes in existence. ((Sophia Pearson and Bob Van Voris, “Google Wins Dismissal of Lawsuit over Digital Books Project,” BusinessWeek: Undefined, November 14, 2013, http://www.businessweek.com/news/2013-11-14/google-wins-summary-judgment-in-digital-books-copyright-case.)) Mainly there is much Google cannot do. Google’s mass digitization currently includes 40 of the largest research libraries in the world. ((“Library Partners,” Google Books, accessed February 24, 2014, http://books.google.com/googlebooks/library/partners.html.)) This method produces a large number of items scanned on a limited footprint, yet misses many items not included in these libraries. 36% of all cataloged books are only held in one library. ((Brian F. Lavoie and Roger C. Schonfeld, “Books without Boundaries: A Brief Tour of the System-Wide Print Book Collection,” Journal of Electronic Publishing 9, no. 2 (Summer 2006), doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/3336451.0009.208.)) With over 100,000 libraries in the United States alone, it is unlikely that all these unique items are at the handful of libraries Google has visited.((“Number of Libraries in the United States,” accessed February 24, 2014, http://www.ala.org/tools/libfactsheets/alalibraryfactsheet01.))

Another challenge with the Google mass digitization project is the “scan now, ask questions later” approach to publisher and author rights. This approach brought about the Authors Guild v. Google lawsuit in 2005. While dismissed in November 2013, it is once again being appealed/ ((Claire Cain Miller and Julie Bosman, “Siding with Google, Judge Says Book Search Does Not Infringe Copyright,” The New York Times, November 14, 2013, sec. Business Day / Media & Advertising, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/15/business/media/judge-sides-with-google-on-book-scanning-suit.html.)) Brethren Digital Archives sought another way, inviting publishers to the table from the very beginning of the project. This partnership has not only avoided possible legal repercussions, but has brought the depth and insight of Brethren publishers and editors to assist with the needs of the project.

Google’s mass digitization project is incredible, and includes many Brethren resources previously available only in the stacks of your local library. However, to successfully digitize the unique resources not available in the world’s elite library collections, local grassroots large-scale digitization projects need to take place. “Large-scale projects are more discriminating than mass-digitization projects. Although they do produce a lot of scanned pages, they are concerned about the creation of collections and about producing complete sets of documents.” ((Karen Coyle, “Mass Digitization of Books,” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 32, no. 6 (November 2006): 242, doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2006.08.002.))

A slow, intentional, dare I say Brethren, approach to such a project does have advantages. Two key advantages are accessibility and quality. Partnering with publishers, Brethren Digital Archives has been able to have candid conversations about open access from day one. Other digitization projects have brought about limited availability to many materials still in copyright, either through a “snippet view” feature or subscription paywalls. Brethren Digital Archives sought to balance the current economic realities of publishers with the desire to have free open access to historical documents, and agreed to have copyright released up to the year 2000 for all publications when possible. Mass digitization without quality control often brings about, as have been chronicled in the The Art of Google Books blog, a variety of errors. ((“The Art of Google Books,” accessed February 24, 2014, http://theartofgooglebooks.tumblr.com.)) Taking the time to select the best available copies of materials, followed by a careful inspection of the scanned product has avoided many of the errors possible with such a project. While aged documents will never look brand new in the digital medium, one can faithfully reproduce what exists.

What remains for Brethren Digital Archives and similar efforts? Plenty. Since Henry Kurtz took to the printing press in 1851 there have been over 250 Brethren periodicals published. Only twenty-seven of these have been digitized. Many of these publications have only one or two known copies, and are quickly deteriorating. Beyond the 250 Brethren periodicals are a world of Brethren affiliated blogs and websites, many of which could disappear today with a click of a button. In some ways the history of the past decade is in a more fragile condition than that of the past three centuries before. The ongoing work of such projects is important to pass on “the faith once delivered to the saints.”

Eric Bradley is Reference and Instruction Librarian at Goshen College, as well as Project Coordinator for the Brethren Digital Archives. His professional interests include next generation library development, theological librarianship, and historical research in the Believers’ Church traditions. He and his son Neil love the Lake Michigan shoreline.