Preached at Washington City CoB, March 4, 2018

Due to the length and variety of scriptural passages upon which this sermon is based, this publication does not include the base passage. We encourage you to examine Exodus 20:1-17, Psalm 19, 1 Corinthians 1:18-25, John 2: 13-22 before reading the sermon, below.

—

The 10 commandments—seems straightforward enough—a list of things to do or not do. Written in stone. Delivered by a notable God/Moses team.

Psalm 19 seems less straightforward , but still comprehensible: 1 The heavens are telling the glory of God.

… and the firmament proclaims his handiwork. –“firmament?” a little less clear not a word I use most days…but in general, I’d give that a pretty high rating on clarity. Even if the particular message proclaimed by the heavens may get occasionally muddled, say, through shifting clouds—oh! Now I see a T-rex… Still, the basic notion that God—who is a creating and sustaining God—can be seen in our surroundings makes sense. Seeing the sunrise provokes a sense of awe, pulling up to the 5a bus stop from Dulles airport and seeing Jenn waiting after a long and harrowing journey, feeling a tiny human move in the belly for the first time. In these, it is not a stretch to imagine that we see hints of God’s presence in the world.

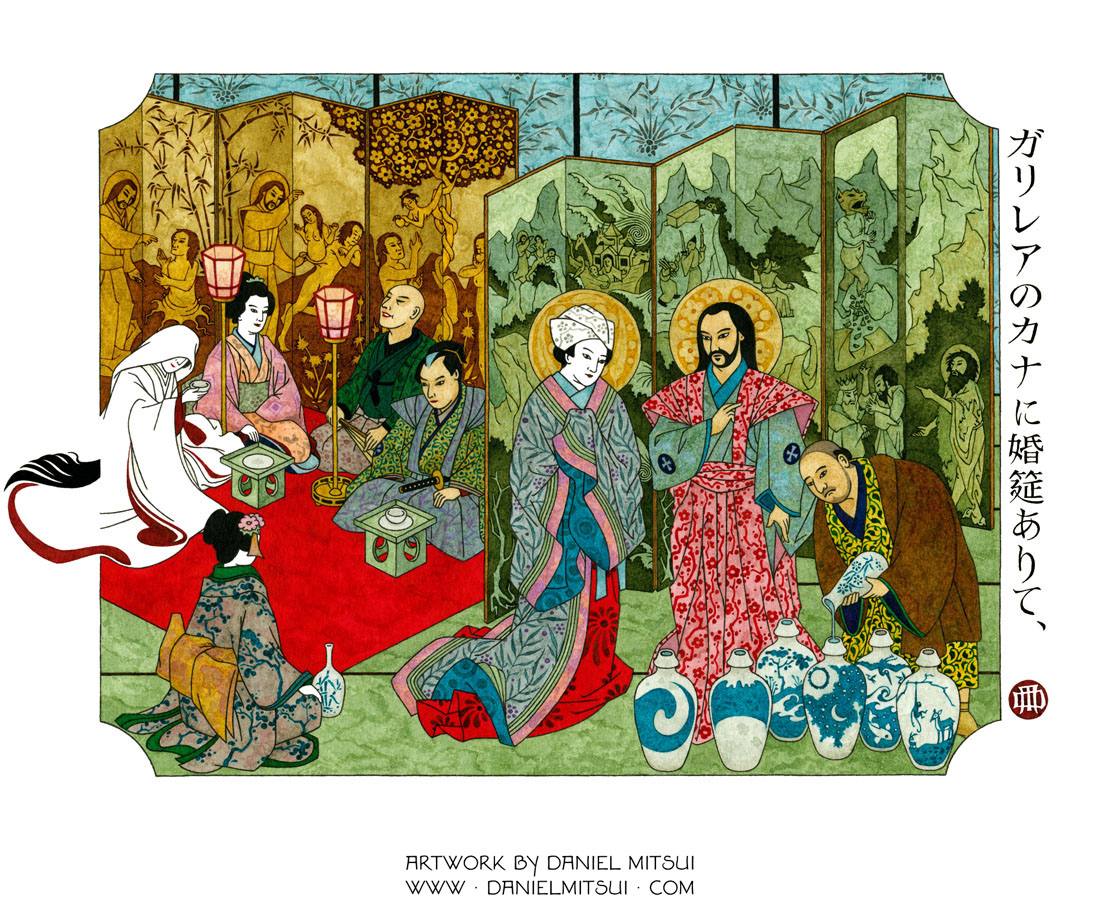

A good God meets us in beauty and joy. In the Gospel of John, Jesus’s first miracle is to sustain the joy of a wedding party in Cana of Galilee. Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky, in The Brothers Karamazov describes, the young man Alyosha, as he prays in despair at the death of his mentor Father Zosima, drifting in and out of sleep hearing the Gospel account of Jesus’ miracle of turning the water to wine at a wedding feast, responds, “Ah, that miracle! Ah, that sweet miracle! It was not men’s grief but their joy that Christ visited, He worked His first miracle to help men’s gladness…’He who loves men loves their gladness, too.’…He was always repeating that, it was one of his leading ideas….’There’s no living without joy,” (Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, 338). The heavens and all of creation are telling of the glory of God.

Immediately after the continuation of the joy in Cana, Jesus acts for justice. Jesus cleans out the Temple. He drives out those misusing the worship space—this seems straightforward . Jesus obviously didn’t like what was happening and did something definitive. Action-oriented, decisive ethical judgements on injustice, clearly communicated. Paired with the first miracle of Cana and at the beginning of the Gospel of John this sets the stage for Jesus’ ministry. In the other three Gospels it is culmination and a building of tension before the arrest and crucifixion of Jesus. [It is also thought to be a symbolic act of destruction. (W.R. Herzog II, “Temple Cleansing,” Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels, 820).

The cross, however, the cross… The cross, which also would seem to be the message, Paul seems to assert that the cross is only comprehensible if one is already being saved. The enlightenment of the cross only makes sense once you’ve reached an understanding which shows that the cross is not foolishness but the power and wisdom of God. In Corinth, the orators, the masters of rhetoric were stars.

One commentator writes, “The world of Paul’s day was deeply enamored with public oratory by virtuoso rhetors known as sophists. Because Christianity placed such emphasis on public preaching, its preachers would inevitably be judged by sophisticated audiences according to the canons of rhetoric.” This performance was one both of word-skill as well as presentation. (B.W. Winter, “Rhetoric,” Dictionary of Paul and his Letters, 820-821). Those who spoke eloquently gathered followers through the logic and beauty of their words (Hays, First Corinthians). Paul, though likely having some such training and demonstrating this skill in his writing—Paul preached without fuss. Paul preaches the foolishness of the humiliating cross.

1:18 For the message about the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.

The 10 commandments cut into stone. Creation pointing towards God. Jesus acting against injustice—seemingly pretty straightforward . The cross—less straightforward . May even intentionally counter how we expect this to go. God is powerful. We expect God to act powerfully—God-like even. Much philosophical reflection on the nature of God through the centuries has focused on the stark difference between finite humans and a powerful, the infinite, the other—God. In the cross,our expectations are turned upside-down.

In the cross our expectations are turned upside-down.

However, at this point, since the cross has now been now used for hundreds of years as a symbol and ornament it may feel clear. Because of this commonality, even when used well it likely has lost its shock. Not only has it likely lost some of the surprise through proliferation, but it has often been used in blatantly bland ways but also in blatantly offensive and abusive ways—with marauding Crusaders or in the burning cross of the Klan, for example. (For bland and offensive at once there is the use of the crusader as a mascot for Christian schools)

If the wisdom of the cross is less clear, how do we get clarity? By staring at it intently awaiting enlightenment? By figuring it out? By describing it eloquently?

Black Liberation theologian James Cone notes that for Jews of the time crucifixion held a place of particular horror, he writes, “Thus, St. Paul said that the ‘word of the cross is foolishness’ to the intellect and a stumbling block to established religion. The cross is a paradoxical religious symbol because it inverts the world’s value system with the news that hope comes by way of defeat, that suffering and death do not have the last word, that the last shall be the first and the first the last…That God could ‘make a way out of no way’ in Jesus’ cross was truly absurd to the intellect, yet profoundly real in the souls of black folk. Enslaved blacks who first heard the gospel message seized on the power of the cross.” (Cone, 2).

Cone writes, “The cross and the lynching tree are separated by nearly 2,000 years. One is the universal symbol of Christian faith; the other is the quintessential symbol of black oppression in America. Though both are symbols of death, one represents a message of hope and salvation, while the other signifies the negation of the message by white supremacy. Despite the obvious similarities between Jesus’ death on a cross and the death of thousands of black men and women strung up to die on a lamppost or a tree, relatively few people, apart from black poets, novelists, and other reality-seeing artists, have explored the symbolic connections.” (Cone, Cross and the Lynching Tree, xiii).

That one community was seized by the cross as an understandable and strikingly similar lived experience, does not necessarily make that understanding either correct or relevant for other groups with a different set of experiences. However, given the way in which this passage overturns the assumptions of the “wise” and the “religious” folks who lack identification in the cross, we, if we are in that group, should be alarmed. Growing up in Sunday School or the Church might not get you there. A seminary degree might not get you there. Flannelgraph might not get you there.

1:19-21 For it is written, “I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the discernment of the discerning I will thwart.” Where is the one who is wise? Where is the scribe? Where is the debater of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world? For since, in the wisdom of God, the world did not know God through wisdom, God decided, through the foolishness of our proclamation, to save those who believe.”

It sounds like we may not get it—we may not get the wisdom of God. For the wisdom and power of God are shown in the cross. Without the cross, we lack all that we need. Returning to Cone, for those of us who allegedly can detach from the suffering of the cross we ought to be alarmed that we may miss God. We are at risk.

The wisdom of the suffering and power of the cross becomes clearer in taking up the cross and following Christ. Taking of the cross and beginning to learn from and even join those who suffer. Cone continues, asking why white theologians have almost wholly missed the connections between the cross and the lynching tree. More specifically he focuses on theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, perhaps the most influential theologian and ethicist of the 20th century, who focused on the cross, wrote about race, and lived in close proximity to large African American communities—pastoring in Detroit during the Great Migration and working next to Harlem, a center of black cultural life. Cone asserts that though Niebuhr wrote about racial injustice he never fully felt it (41). He showed little interest in actually getting to know black folks. He writes, “It has always been difficult for white people to empathize with the experience of black people. But it has never been impossible.”(Cone, 41). This beginning to understand is not simply understanding a social analysis of an “issue” but digs deeper into even understanding God. Understanding the very nature of the way that God has worked and how we participate is at stake.

The Jews, having lived under the oppression of both military occupation and forced exile understandably expected and hoped for the Messiah to come with political force and set up a righteous kingdom where they were in power. The Greeks wanted elegant and beautiful rhetoric to convince them. However, as Cone writes, the cross inverts the expectations and values. The cross is not only not this but would seem to be the opposite—foolish and weak.

“But to those who are the called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God.” Jesus invited his disciples to “take up their cross” and follow him, Christ calls us to be present with him in being with those who suffer.

God’s foolishness is wiser than human wisdom, and God’s weakness is stronger than human strength (v.25).

Devotional/Application Questions

- How have you seen God, or experienced God’s presence, in the seemingly mundane?

- In what ways do you appreciate “set-in-stone” commands?

- How does God, as expressed through the Gospels, surprise you?

- How does the cross reorient your understanding of power?

- For what sort of messiah have you mistakenly looked/hoped?

- How is the peculiarity of the Christian God foolish, or even a stumbling block, for those not in the faith?

Nathan Hosler coordinates the Office of Public Witness for the Church of the Brethren denomination. The office’s work is summed up in the tagline “seeking to live the peace of Jesus publicly.” Nathan has a BA in Biblical Language and and MA in International Relations. He is currently working on his PhD in Theological Ethics. Nate prefers to run long distances, have several books started at one time, and eat food from around the world.

Nathan Hosler coordinates the Office of Public Witness for the Church of the Brethren denomination. The office’s work is summed up in the tagline “seeking to live the peace of Jesus publicly.” Nathan has a BA in Biblical Language and and MA in International Relations. He is currently working on his PhD in Theological Ethics. Nate prefers to run long distances, have several books started at one time, and eat food from around the world.

For more of his sermons and other writings, check out the Washington City Church of the Brethren.