Chibuzo Petty

How do you understand the difference between writing and writing as ministry?

Nick Patler

I am not sure I can explain the difference. For me, particularly as a historian whose interest is largely in African American history, writing is about telling stories, giving voice to persons and narratives that have been suppressed or whose legacies and contributions have been maligned. It begins with deep exploration and with being honest. Is that a form of ministry? I guess it can be, particularly since it gives readers a chance to step into other contexts and thus to humanize those who have often been marginalized and whose lives and contributions have been erased or misrepresented. Writing stories in African American history is also about deconstructing and subverting white supremacy since silencing Black history, or telling lies about it, as whites elites and academics did for generations, were used to construct and maintain the edifice of Jim Crow and systemic racism. I don’t mean here that I am politicizing history, or writing with an agenda when I talk about subverting; I simply mean that by allowing the true narrative to unfold, getting closer to the truth of history, allowing it to resurface, naturally challenges beliefs and structures and it dismantles lies.

I remember I was asked at Bethany Seminary what my methodological approach was to writing history. While I understand this has relevance in academia and with scholarly writing, I could not answer that question. I explained instead that I dig into as many sources as possible, and allow the voices, participants, and events to tell the story. I likely have an unconscious methodological bent, but I do not select a specific methodological approach when researching and writing. I like to think that the methodology evolves or adapts to the story as it unfolds. In short, the tools and lenses adapt themselves to the needs of the story, of history-telling.

I think maybe one example where I had difficulty here is when trying to transform my Bethany thesis on the Underground Railroad into a book. Something was off with that adaptation process, and even my writing did not seem very good – something bland, wooden about it – and I was not pleased. Something also seemed bland even in an article I wrote about it for an Indiana historical magazine. After engaging in one peer review that was pretty critical, I decided maybe I should leave this one a thesis. And yet I am having the opposite experience with the book I now have out with the second round of peer review with University Press of Mississippi on PBS Pinchback and Blanche Kelso Bruce, two Black leaders during the Reconstruction Era, where they took over the story as I was writing it and to me seemed to move the narrative forward with life and action.

Chibuzo Petty

We’ve previously explored the writing process through a piece titled “A Look Behind the Curtain: Three Writers Reflect on the Writing Process.” How might you respond to the themes explored in the linked publication?

Nick Patler

I don’t really reflect much on my writing process. But I am fascinated by how you, Karen, and Emily explain your writing processes! As a historian, I dig, dig, and dig some more, and then allow the story to unfold. I usually accumulate what I would describe as many puzzle pieces, and then allow them to connect and the story to unfold. My first draft tends to be full of long sentences and paragraphs, and then I rework them after that. I have a bit of your OCD, Chibuzo, in that I obsess over paragraphs, sometimes spending days reworking and reshaping one or two paragraphs. I also obsess over representing the people I am writing about as authentically as possible. I try to let them speak for themselves – and be themselves – as much as I can glean from the historical sources, including how they navigate their contexts. I also like how Karen describes it as madness at times. Indeed! Sometimes to get the story right is like walking a tightrope backward while wearing a blindfold. It all feels so unsteady and dark at times, and I sometimes wonder if I will survive it all. But then there is usually a balance and clarity that occurs the more I stay with it and trust my instincts and research, and much joy in the process when it comes out right. The hardest part is getting it ready for the publication process, particularly when going through peer review, which can be grueling since experts in the field scrutinize your work before publication. But after the shock and “who the hell do they think they are” wears off, I realize that they are right, and adhering to their suggestions and guidance makes the manuscript better. I am always amazed how writing is in many ways a community process, from those who made the history, to engaging sources left behind or produced by other people, to build on the works of others, to the involvement of experts in peer review, and on through the involvement of copy editors. And, of course, the readers and those with who I share my work with at talks who always contribute good insights, often enabling me to see my own work in different ways.

Chibuzo Petty

Thanks for your affirmation. Your thoughts are very interesting. I definitely can appreciate and relate to much of what you said.

Now, another question. How did you come to be associated with the Church of the Brethren?

Nick Patler

I found the Church of the Brethren after becoming disenchanted with mainstream churches and religion, particularly conservative evangelicals. I started to fall away when I was a student at Liberty University as I saw so many Christians and an academic institution embrace militarism and the destruction of enemies, all the while praising the Lord in chapel and worship when it seemed to me Christ taught something radically different. It also seemed to be interwoven with racism – there was something so blindingly white about it – and awash in hyper patriarchy. The Christianity that I was in the midst of seemed inspired by fear and judgment more than love, and I checked out for most of the time I was there. I gradually began to reconnect with my Christian tradition through old tapes of sermons by Dr. Martin Luther King. I often tell people that white folks almost ruined Christianity for me and the Black church saved it for me. Eventually, my mother and I both wanted to find a church, one that adhered to love, peace, and nonviolence, and soon felt led to try the Staunton (Virginia) Church of the Brethren. It was ok at first, but the more I went the more I felt at home and connected with the Anabaptist tradition and the people. Not only was the COB a peace church, but I was impressed that they were so service-oriented with disaster relief ministries, going places to help others who were in need. From there the COB became my church, and I still consider it my church to this day.

Chibuzo Petty

It sounds like we had similar paths. I come from a contemporary Evangelical mega-church background. Though peace is certainly valuable to me, I actually was most drawn to the Historic Peace Churches because of their longstanding emphasis on simplicity (and, even, modesty). I found my way to joining a Quaker meeting. When I received the call to seminary, I considered moving out west to attend George Fox Evangelical (now known as Portland Seminary) but it just wasn’t feasible at the time. After applying to Earlham School of Religion, another Quaker graduation institution much closer to where I was living at the time, it became clear that, in many ways, I would have been a theological outlier. I was encouraged to explore a relationship with Earlham’s sister school Bethany and that’s how I came to the Church of the Brethren. I have worked for a variety of Brethren organizations and congregations since. It is interesting, in the Catholic Church once you are baptized you are a member for life unless you formally reject that membership in some way. In the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) the term for those who convert to Quakerism, that is those not born into the faith community, is called being “convinced.” In that respect, I still consider myself a Quaker as I have never become unconvinced of the radical truth that there is one, even Christ Jesus, who can speak to my condition and that he has, indeed, come to teach his people himself as Quaker founder George Fox said. Quaker’s emphasis on personal piety has made it easy to connect with Brethren’s Radical Pietist roots.

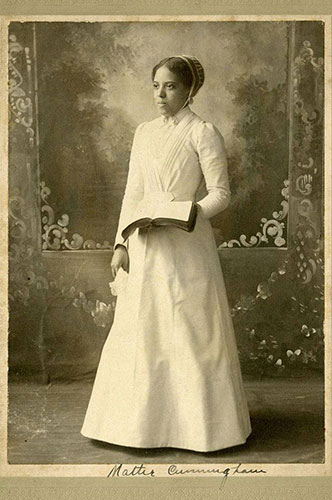

I would like to move now to your recently published article about Mattie Dolby (link featured at the end of this piece). What drew you to this subject?

Nick Patler

Karen Garrett inspired my interest in Mattie Dolby. Karen really appreciated my love for African American history, even nurtured it at Bethany, and she told me about this remarkable woman in Brethren history who she thought I would find interesting. She gave me a copy of Midred Hess Grimley’s 1976 essay on Mattie Dolby–I believe it was from the Messenger, and I was fascinated by Dolby’s determination, courage, and power to navigate a white church, push its boundaries to accommodate her vision and ambition, and to do this at a time when Jim Crow was at its zenith, so intensely oppressive, violent, degrading. Then while taking Brethren History with Denise Kettering-Lane, I wrote my final research paper on Mattie Dolby with Denise’s encouragement and oversight. I felt deeply drawn to Mattie Dolby, and wanted to give voice to her–to uncover that authentic voice as much as possible. I felt that while Grimley’s 1976 article was groundbreaking–I stood on her shoulders to write my own essay–the central theme, used it her title, that Mattie Dolby “sounded no trumpet”, just did not sit well with me. I felt that Mattie did speak loudly, or sounded the trumpet, about the indignities Black people faced, the racism of her day, in different ways. She was not a direct confrontational activist, indeed, very few people were in that day, with the exception of a few like William Monroe Trotter, but she protested and spoke with her pen where she integrated the great Black thinkers and writers of her day as parts of her own voice, such as W.E.B. Dubois and Ida B. Wells, in her many articles she wrote for the Gospel Messenger and the Missionary Visitor. She expanded the horizons of her congregations, sharing her study and exploration of Black history, as well as educating them so they would not be so vulnerable to white supremacy, and she eventually protested with her feet when she and her family left the Brethren Church.

Chibuzo Petty

Throughout the article, you discuss how Mattie Dolby sojourned between Friends (Quakers), Brethren, and African Methodist Episcopals. For many, the connections between Friends and Brethren are well understood. How do you make sense of the decision to leave a particular faith witness, and its accompanying theology, for a sort of ethnic safe haven of a denomination?

Nick Patler

As I mentioned in the essay, I believe it took something major for Mattie Dolby to leave the Brethren Church, an institution that was an intimate part of her religious identity for over 40 years. And what contributed to that severance from her tradition was, I believe, racism and humiliation, particularly at the Springfield Church but also likely because of an accumulation of racist experiences, including what today we would call microaggressions. I tend to think that being asked to leave the Springfield church was the tipping point for Dolby and her family. The Brethren Church was a white institution, as it proved itself to be, set in its ways with its roots deeply embedded in a different history and experience. Their structure and committees, dominated by whites, were not well suited for black growth and development, and it was only willing to go so far in confronting and transcending its racial biases. The Dolbys did what many African Americans did: they went where their interests and needs were met, where they were welcome and sought after, and where they could have a voice in their affairs in community with others who shared similar experiences and goals. The AME was an expanding space that was well-adapted to meet the material, educational and spiritual needs of African Americans, free of white control and the humiliation of racism.

Chibuzo Petty

You mention Interim President Inkenberry being influenced by lynching in his decision to integrate Manchester University. Apart from Dolby, what other ways were a Peace Church response to lynching lived out at Manchester?

Nick Patler

Well, I surmise that he was considering the context of the times. I am not sure what other ways Manchester responded to the lynching that was happening, as well as the rising tide of aggressive racism. It would be interesting to look into, particularly since Mattie and her brother Joe may have helped nurture a sensitivity to these issues among their white peers.

Chibuzo Petty

How do you understand the relationship between Dolby’s experience with the economics of ministry and modern concerns regarding philanthropy, capitalism, income inequality, reparations, and redistributive economics?

Nick Patler

Mattie Dolby certainly saw a connection between white money and resources and advancing the interests of African Americans, modeling her approach after Booker T. Washington. She believed that philanthropy was important, and she tapped pockets that could afford to help in the Brethren world. However, while some help was forthcoming, economic and ministerial outreach to African Americans appear not to have been a serious priority in the COB. This lack of commitment was a reflection of how most of the white world in the U.S. felt about its responsibility to African Americans which continues through this day. I would say that racism relegated African Americans to the bottom of national or collective priorities, except that in many cases they were no priority at all, as resources were intentionally withheld from African Americans – resources whites had access to – often with the threat of violence if they should try to access them, such as economic status and voting (power). In the South, as Dolby discovered, whites wanted to keep African Americans poor and ignorant (and then the right to complain about it), a cheap source of labor as well as at the bottom of the social hierarchy to elevate themselves, even the poorest whites who could rest assured that the law and custom of the land guaranteed them that their status was always higher than that of African Americans. And while philanthropy at the urging of Booker T. Washington was forthcoming in that day, the catch was only if African Americans would submit to a second class or inferior status, and usually only if whites had say or some control and oversight in the Black institutions where white money flowed. This included HBCUs. Considering all of this, there were no serious attempts at reparations for African Americans, no redistribution, and, consequently, income inequality was a perpetual abyss from that day to our own.

That is why the issue of reparations is so vitally relevant today. It is an ongoing moral and economic issue because at its core was the violent oppression and withholding of resources and opportunities for African Americans, centuries of deprivation, as well as the stealing of labor, from slavery to Jim Crow to redlining, etc., while at the same time whites were allowed to prosper and access resources with no penalty. One hand was lifting up whites as the other hand pushed African Americans down. It should be a no-brainer that this caused severe economic inequality, incredible hardship, dangerous and lethal racist structures and institutions, which we still see today, and thus we have a serious responsibility to address it with intention and focus and to work towards equity and justice without stopping until we achieve it.

Chibuzo Petty

We’ve previously explored the themes of money in urban and intercultural ministry in a piece titled “Paul, Money, and You: A Reflection on Intercultural Stewardship.” Do you have any further reflections to add?

Nick Patler

Gosh, this is a thought-provoking piece! I did not know that most tithing is well below the 10 percent standard in Hebrew Scriptures. I wonder if the giving increases when we consider other needs and humanitarian causes outside of the church? Also, it does not surprise me that those in lower-income brackets give higher percentages than those who are in higher ones. I also share your interest in establishing entrepreneurial ministry training programs. I think of what Simon Thiongo is doing in Kenya (Earlham School of Religion graduate 2015), which is essentially just this, and how he is helping impoverished people and families become self-sufficient through farming and raising animals and livestock.

Chibuzo Petty

Thanks, again, for your affirmations and insights. Readers interested in learning more about Simon Thiongo and his work should read his Asbury Theological Seminary DMin dissertation “The Role of the Church in Poverty Eradication in Kenya: A Focus of A.I.C. Kijabe, Region.”

As we near the conclusion of this conversation, what is one thing not covered in your article that you want people to know about Mattie Dolby?

Nick Patler

The thing that I want readers to keep in mind is that while Mattie Dolby was a leader, a church planter, a deep thinker, someone who overcame obstacles to flourish and to uplift others, I believe she also lived with a certain sadness and perhaps even depression that I don’t think comes through in my piece. In addition to the pain and humiliation of severing herself and her family from her denomination tradition after four decades, not long after leaving the COB she lost her husband Newton prematurely after he died of a heart attack. This was her love and her partner in ministry and she never remarried. She had also lost her younger sister Lulla Belle years earlier, who she had been very close to and whose premature loss impacted her deeply. Once Newton passed, Mattie Dolby often struggled financially and this appears to have continued for years making living more of a challenge than it had been when Newton was alive. I sense a certain sadness about her after all of this, particularly when Newton passed. Yet, she kept going and continued to lead congregations and impact lives immeasurably and left a powerful legacy of service and commitment for her family, for those she ministered to, for all of us.

Chibuzo Petty

Thank you so much, Nick, for taking the time to discuss all these interesting topics with me. I have found our time together incredibly enriching and trust our readers will too!

To read Nick’s article, “Recovering African American Voice and Experience in Brethren History: A Biographical Essay on Mattie Cunningham Dolby 1878-1956,” or to donate or subscribe to Brethren Life & Thought’s print journal click here.

Rev. Chibuzo Nimmo Petty is a creative, organizer, and minister whose passion is the intersection of cultural competency and pastoral care. He and his family live in Cleveland, Ohio. You can find his writing and editing work in the Church of the Brethren’s bi-annual academic journal Brethren Life & Thought or more regularly on its affiliate blog DEVOTION.